Three weeks ago, we received an influx of incredibly helpful feedback from founders after Paul Bassat reached out to the community via this LinkedIn post.

One recurring theme in the feedback that resonated with me was: telling founders you invest early is actually not that helpful. Founders asked: what does ‘early’ mean? What does ‘seed stage’ mean? Are you meant to have any traction at the ‘early’ stage of a startup?

A huge challenge for founders is that every fund has different answers to these questions.

I wanted to make the answers to those questions less opaque by sharing our data. I went through the 10+ year history of Square Peg’s investments, and reviewed all the investment papers the team had written to understand what we knew about the companies at the time we invested. Here’s what I found.

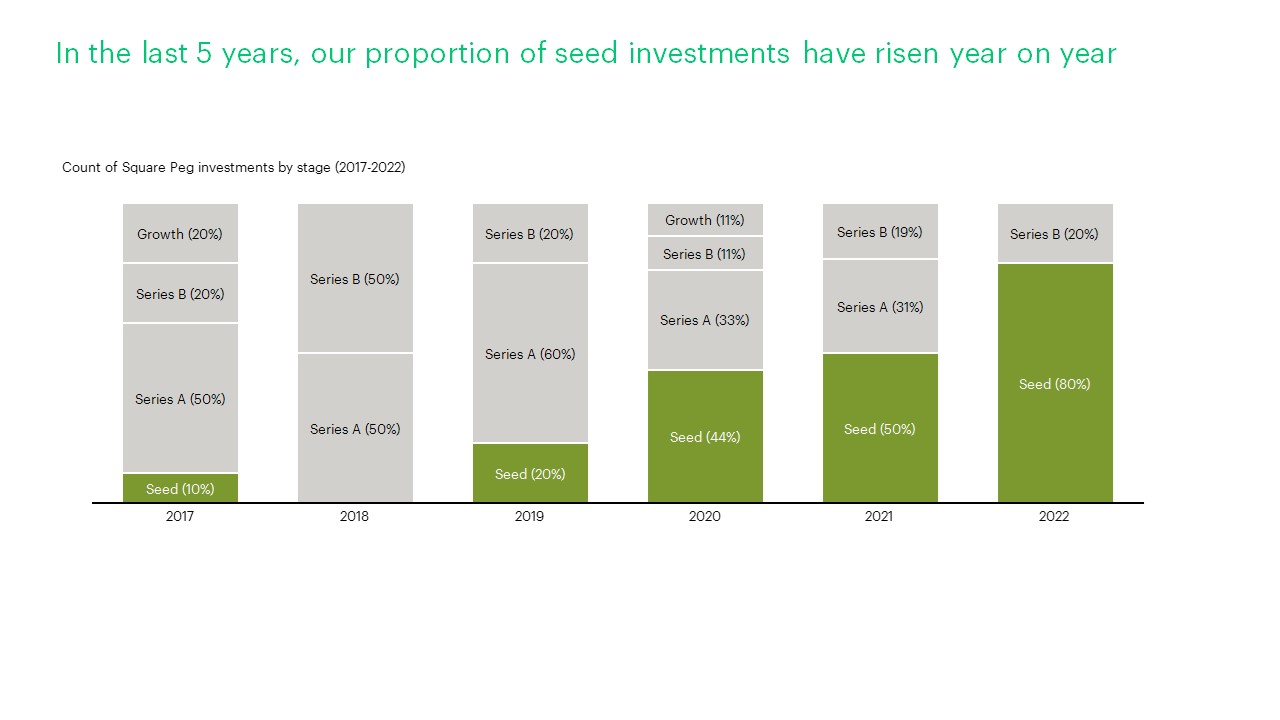

1. Our investing behaviours have changed over time

In the last 5 years, the proportion of investments into seed rounds has risen year on year to now form the majority – in 2022, seed represents 80% of our new investments.

2. When we do invest at seed or Series A, we tend to write larger cheques (US$1m+)

Our historical data from 2012 to 2022 showed that approximately 40% of our initial investments in a startup happened at the seed stage.

But labels like ‘seed’, ‘Series A’ or ‘Series B’ can be unhelpful because cheque sizes and valuations associated with stages change over time depending on market cycles. Therefore, I show below the breakdown by cheque size as well.

When we invest at the seed stage, we tend to write cheques of more than US$1m. Dan Krasnostein, our Melbourne partner, recently wrote a great post here explaining why that is the case. In short – we are high conviction, high commitment investors. We don’t do small cheques to “test the water”. We only invest when we are so excited that we are banging our hands on the table to partner with you.

As a founder, that means you can expect us to drop everything to be helpful to you. We are empathetic partners who are there with you for the long journey – both the ups and downs.

The other factor to keep in mind for current round size is what the next round looks like (i.e. what milestones does the founder need to hit to make the next round a success, and how much money do they need to get there). A larger round can often give founders more buffer to experiment and make room for high value angels or seed-focused funds. That being said, a small round is better than no round. Pragmatism wins above all: founders have to make the best decision with the options available to them.

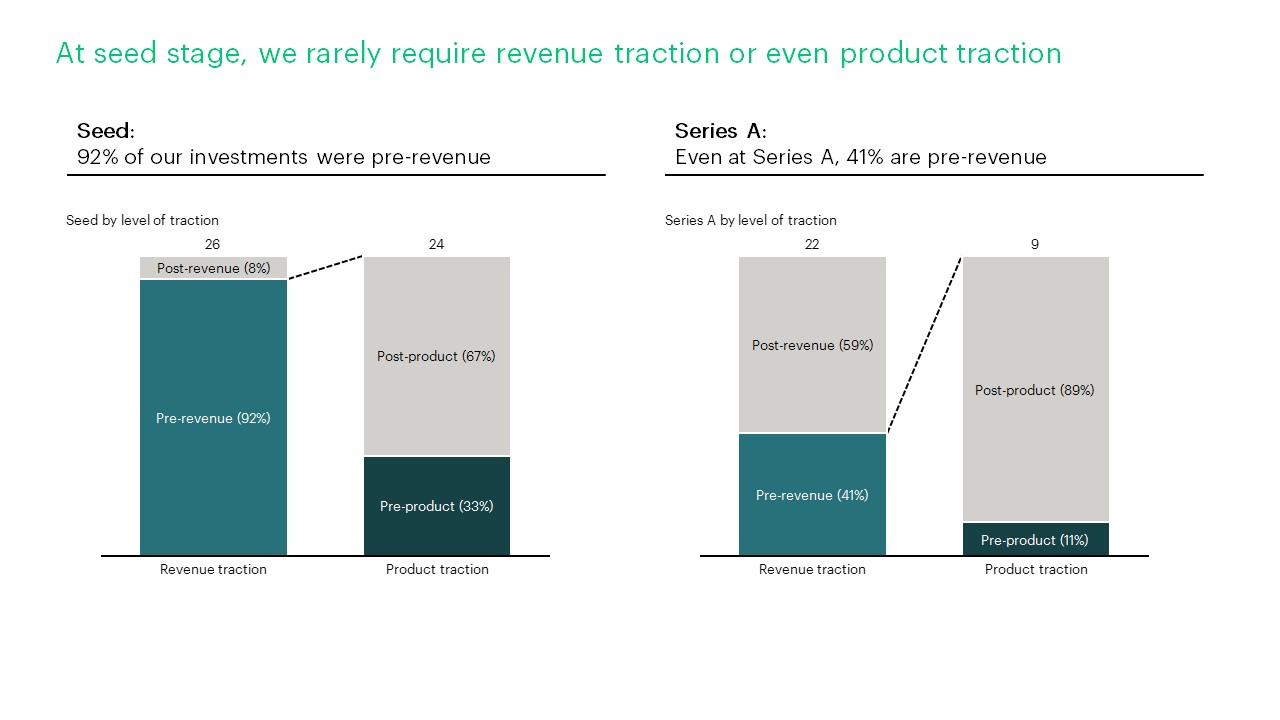

3. We don’t need to see revenue traction at seed stage

Traction can be an unclear term to founders because many funds will demand to see different levels of ‘traction’ for the same stage.

A common demand to founders may be to come back when there’s revenue. Looking back over the past 10 years, that has not been a demand we make to founders. In 92% of our seed investments, we have invested pre-revenue.

We also look at other signals, for example:

- The depth of a founder’s insight into the problem;

- Whether the hypothesis on the solution is compelling and differentiated; and

- The level of ambition and the plans around achieving it.

Founders don’t need to have all the answers. Often, we’re impressed by founders who are aware and upfront about the risks, as well as what they know and what they don’t know.

Here are some examples of investment into seed businesses and the reasons behind them (the founder archetypes range quite a bit!):

- Saasguru (pre-revenue) – first-time tech founders with a background in cloud consulting. They had deep insight into the cloud skills gap, as well as an approach that went beyond the “digital textbook” model of first-gen ed-techs.

- Vow (pre-revenue and pre-product) – the founders came from outside the industry they were tackling, which gave them a fresh perspective and a novel strategy to solve the future of food with cell-based meats.

- Zeller (pre-revenue and pre-product) – a seasoned team that had come out of Square, looking to build a payments solution that they had strong domain expertise in.

What’s common in these investments is not that “we’re looking for a founder who has done X, Y, Z or comes from A, B, C background” but that they all demonstrated a unique insight into the problem and a compelling, differentiated hypothesis on how they would solve it.

What should founders take away from all this?

I hope that by sharing this data, we have at least made Square Peg’s definition of ‘early’ more clear to founders.

The broader message I want founders to take away though is that when we say we are ‘high conviction’ investors, that does not mean we need to see a post-product-market-fit business where the revenue is flying. It simply means that we do have to say ‘no’ a lot when we can’t get to that level of high conviction. However, when we say yes, we are fully behind you for the first and subsequent rounds.